This paper describes Grendel, a powerful Python-based interface to Cisco's 802.11a chipset. Python has enabled the rapid and continuing development of this tool. Grendel has dramatically reduced the time required for a team of engineers to develop and debug powerful and sophisticated integrated circuits. Moreover, Python's ease of learning has allowed hardware engineers to capture design knowledge in Python scripts without the intervention of Grendel's authors.

Cisco has developed a two-chip implementation of the physical layer for an 802.11a wireless LAN system. IEEE 802.11a is a specification for wireless LANs operating at up to 54 Mbps in the 5 GHz radio band [1]. Cisco has developed an 80 MHz baseband processor (the modem) and a 5 GHz CMOS radio processor (the radio) [2]. The development of these systems was an extremely demanding technological challenge; the technology is novel, and market pressures demand a solution that is cheap, low power and delivered as early as possible. Adding to the difficulty is the fact that the 802.11a specification wasn't finalized - was in fact highly fluid - when chip development started. The lack of a concrete specification lead to a highly configurable chip architecture: many parameters of the chips can be configured through software.

Grendel is the GUI tool which supports a diverse team of engineers (digital, analog, system and test) in the development of these chips: from FPGA prototype, first silicon, reference design and then into product. Grendel is a vital element of the chip development process, dramatically reducing the time required for chip development and debugging. Grendel is both powerful and approachable; it can be immediately used without training by an engineer, but it also provides flexibility and extensibility for advanced users.

Grendel is written in Python 1.5.2; the GUI portions are in JPython 1.1, with the underlying hardware interfaces written in C. Currently, Grendel runs only on Linux.

It's efficient

Grendel's principal interface to the user is a GUI, although a script or command-line interface is available; the following sections use the name Grendel for the GUI portion. By providing a graphical interface to the chips in a form readily understood by humans, Grendel accelerates and empowers the difficult (and time-critical) chip development process.

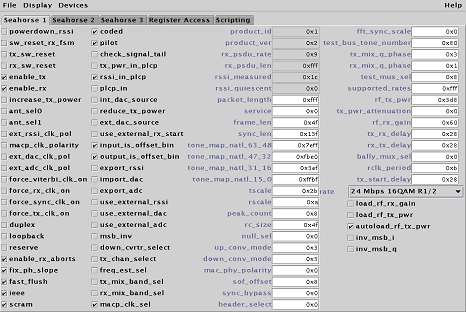

The Cisco 802.11a chips are configured by writing to on-chip registers. In this context, a register is some range of bits in a word at a given address; several registers can be packed into a single word. Each register has a name that reflects its function. Grendel's GUI displays the registers with names and values. Values are displayed as decimal or hex numbers (user selectable), as checkboxes for single-bit quantities, or are mapped to some non-numeric textual form.

Grendel's register abstraction presents the chip configuration space as names rather than as addresses. This is attractive because the register names reflect function; these are much easier to remember and work with than numeric register addresses. By showing the names of the registers on the screen, the GUI provides a visual prompt to the user of the available functions. By hiding the addressing details of the registers, the user doesn't need to worry about shift and mask operations when multiple registers are packed into a single address.

Grendel also supports saving and loading the configuration state of a chip to a file. This allows the users to reliably put the chips into a particular state (across power cycles and different chips and different test setups). This feature also serves to encapsulate knowledge; a filename now maps to a particular configuration without users needing to understand the details. For example, the file named digital_loopback.config puts the chips into a digital loopback configuration - this requires numerous changes from the default state of the chip, but the user doesn't need to know about these changes to use the saved configuration. Further, for testing and debugging it is crucial that the system can reliably be put into a particular state as required.

Grendel completely hides from the users the complexity of the varying hardware interfaces to different test boards. This is an important win because the user isn't distracted from the interesting issue of testing and debugging the chip by the complex but irrelevant differences in the hardware interfaces.

It's powerful

As well as exposing the on-chip configuration registers, Grendel provides a mechanism for editing and executing arbitrary Python scripts from within the GUI. These scripts have access to the chips through the same interface as the rest of the GUI (the details of this interface are described below).

User scripts are a powerful tool for allowing the users to encapsulate knowledge: complex operations can be captured as a script, or a function within a script. Once these have been developed, other users can use these functions or scripts without having to worry about the details of how they work. This encapsulation is a huge efficiency win, because it allows users to reap the reward of effort invested by other users.

It's also important that these scripts are developed by the users themselves, rather than the original Grendel authors. This prevents the Grendel authors from becoming the bottleneck in this process. It also allows users to bring to bear knowledge from outside the Grendel authors' software engineering domain.

By making the scripting feature part of the GUI, users can develop code incrementally, and see the effects of the code on the chips (using the GUI) as they develop the code. This wouldn't be so simple if they had to modify the Grendel code itself.

It's honest and forgetful

The Grendel GUI is honest and forgetful; it always displays the real state of the chip, and doesn't try to remember it. When a users writes to a register, the GUI element involved is then updated by reading back from the chip. Similarly, when the GUI is refreshed, every register is re-read from the chip; Grendel doesn't try to remember the state of the GUI. This is critical because it prevents the GUI from deceiving the user; if there is a hardware problem (not uncommon in a hardware development context!), this must be reflected in the GUI.

(Almost) everything is Python

As described above, an important feature of Grendel is the ability to save and load config files that record the complete state of a chip. This is implemented by writing to a file a sequence a Python commands, that, when executed, set all of the on-chip configuration registers to the appropriate value.

modem.rx_mix_q_phase = 0x2 modem.adc_standby = 0x0 modem.down_conv_mode = 0x3 modem.enable_turbo_code = 0x0 modem.enable_direct_conversion = 0x0

This approach has several advantages: reading, parsing and loading the input file just consists of a call to execfile(). This is fast, has powerful error detecting and reporting facilities, and was pretty quick to write! It is also means that config files can be augmented by arbitrary Python code to produce 'intelligent' configs. For example, config files can be modified to set the appropriate configuration values depending on the version of the chip being used.

Another example of the re-use of Python's parser is in the input boxes in the GUI. Text input is checked, parsed and evaluated using the following code:

integer_type = type(42)

try:

value = eval(self.textbox.text)

assert type(value) == integer_type

return value

except:

return None

The obvious candidate for this task, the string.atoi() function, was not used because Grendel's GUI was developed under JPython-1.1, where string.atoi() didn't correctly deal with hex inputs (it's fixed in Jython-2.0). It's still used because it provides a feature which was discovered by the users, much to the surprise of the Grendel authors: textboxes can understand simple arithmetic expressions. Users discovered that they could type in expressions like 64+7, or (1<<15)|0xBEEF, which are occasionally useful.

The Grendel approach of using Python's parser has been successful because there is a good match between the fairly simple requirements of the config files and the parser. This is not, however, a universally applicable approach; see for example Eric S. Raymond's discussion of his decision not to use the Python parser for the CML2 language [3].

The register-level abstraction

The Cisco 802.11a chips are, as described above, configured by writing to on-chip configuration registers. A register is some range of bits in a word at a given address. There are also readonly registers which provide status information from the chips. Grendel uses a simple container class, Register, to hold the bit range and address of a register.

Grendel builds the register abstraction layer as follows. An instance of a class Chip represents a single chip. A Chip instance is defined by a set of Register objects, an interface object, and an ID number to identify the chip on the board. The Chip class implements __setattr__ and __getattr__ to allow named registers to be used:

# create an interface to the modem modem = Chip( register list,…) # reset the chip modem.reset = 1 modem.reset = 0 print "version number is", modem.version_id

The Chip class uses a dictionary of registers to map a named register to a bit range and an address. This address is then passed to the interface read or write function, and the result fed into the appropriate shift and mask operations.

As well as registers, Chips contain RAM objects. Parts of the configuration space of the chips are small RAMs. Rather than being represented as a sequence of named registers, the RAMs are represented as RAM objects which support slicing operations. This allows the RAMs to be addressed in a natural way:

modem.preamble[0] = 24 modem.preamble[23] = 0x47

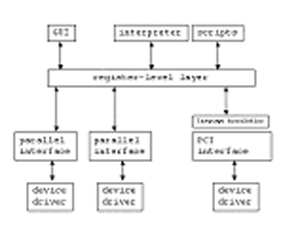

Interfaces

From a configuration perspective, a chip consists of a set of registers and a mechanism for talking to the chip. The mechanism for talking to the chip depends on the system in which the chip is embedded. For example, some testboards communicate with a host PC through a parallel port interface, and others through a PCI interface. In Grendel, the mechanism for talking to the chips is an interface, which is an object which knows how to read or write an address in a given chip. Actually, interfaces talk to boards; a numeric ID is used to distinguish which chip on a particular board is being addressed.

Each of the interface objects presents the same interface to the register-level layer above it. The interface objects are implemented in Linux as device drivers written in C. The device drivers handle the timing and handshake issues with the hardware. The parallel interfaces are implemented as character devices, which Python communicates with by doing file I/O on /dev nodes. The PCI interface, however, communicates through C functions. For standard C Python, this simply requires a simple C extension module. For JPython, however, the situation is a little more complicated. It is trivial to get from JPython to Java; getting from Java to C requires Sun's JNI (Java Native Interface) [4]. While this is not fundamentally difficult, it's annoying because it presents a maintenance issue. The Python-C and JPython-Java-C interfaces must be kept synchronised, with no language or automated support for doing so. Automating some or all of this process, using for example some SWIG-like tool, is an interesting possibility for future work [5].

Thus the lower layers of Grendel consist of the register-level abstraction, which sits above a set of interchangeable interfaces. Above the register-level layer sits either a GUI, or simple scripts exercised from the command line, or an interactive Python interpreter. The remainder of this section describes the GUI in some detail.

GUI architecture

The GUI part of Grendel is implemented in JPython; this gives us access to Sun's Java AWT widget library [4]. The GUI consists of a set of tab panes. Each chip has a corresponding pane (or panes) that represents the registers in the chip. Most registers are represented using a simple numeric entry box (for multi-bit registers) or checkbox (for single-bit registers). Readonly registers are represented with display-only widgets. A few registers are represented by more advanced widgets that map the numeric value in the register into text. These can be seen in Figure 1.

As well as panes that show a direct representation of the registers of a single chip, there are several panes that provide higher-level functions:

An earlier GUI for an FPGA prototype system was developed in Tcl/Tk. This GUI quickly evolved into a large monolithic chunk of code, liberally sprinkled with global variables and functions. Apparently minor changes were causing name clashes which would cause the software to silently Do The Wrong Thing. At this stage, it became clear that Tcl's limited language support for large, modular programs was a problem. A new language was required that:

An analysis of these requirements lead us to choose Python, with JPython for the GUI elements. The experience of developing Grendel has highlighted several other powerful advantages of Python.

Rapid, just-in-time development

Grendel has proven to be amenable to rapid changes in response to changing requirements. This is partly because Grendel's modular architecture means that new features can easily be slotted in. Because of Python's good namespace protection, there is no risk of changes to one part of Grendel breaking some unrelated part. For these reasons, Grendel can be rapidly extended in response to growing user requirements. Further, because new features can quickly and safely be added to Grendel, users get 'instant gratification'. New features can be added without the need for a long involved planning process. This rapid response dramatically decreases chip development time.

Robust

Python has proven to be robust in the following sense: Grendel has been developed as a series of rapidly developed, "I need it NOW" features. It has survived this onslaught without becoming a fragile mess of spaghetti code.

Python is also robust in the sense that Python scripts don't crash. When the Grendel GUI encounters some bad input, or hits a bug in the code, it raises an exception, prints an error message, and keeps going, rather than throwing core. From the user's perspective, Grendel recovers gracefully from bad input. From the Grendel author's perspective, it means that a lot of work doesn't need to be put into validating input because Python will deal gracefully with bad input. It also helps to make Grendel robust and rapidly extensible; an error in one part of the GUI won't usually hang the whole GUI.

Accessible

Python scripts running within Grendel represent a large accumulation of knowledge about the chips, encapsulated in a re-usable form. The scripts have largely been developed by the users, rather than the Grendel authors. This is important from a company perspective - the Grendel authors aren't a bottleneck - and interesting from an educational perspective because this work was done by people who were not Python programmers; in fact, most of the work was done by people who wouldn't even describe themselves as programmers, but rather as system engineers or hardware engineers. Python is easily learnt by non-programmers, at least partly because working, useful, scripts can be developed by copying an existing script and making changes. Python supports this easy learning curve through a clear, regular and fairly verbose syntax, good error reporting, and robustness (the fact that bugs in a script won't crash the GUI enables exploration).

The development and debugging of powerful, complex chips requires powerful, simple software tools. Python, through Grendel, provides this tool.

It's also perhaps interesting to note that in the development of Grendel, the Grendel authors have become huge fans of Python!

[1] IEEE Computer Society. Draft Supplement to Standard for Telecommunications and Information Exchange Between Systems -LAN/MAN Specific Requirements - Part 11: Wireless Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications: High Speed Physical Layer in the 5 GHz Band. 1997.

[2] Philip Ryan et al. A Single Chip PHY COFDM Modem for IEEE 802.11a with Integrated ADCs and DACs. ISSCC 2001.

[3] Eric Steven Raymond. The CML2 Language Constraint-Based Configuration for the Linux Kernel and Elsewhere. Ninth International Python Conference, March 2001.

[4] Sun Microsystems. Java 2 Platform API Specification. http://java.sun.com/j2se/1.4/docs/api/overview-summary.html.

[5] SWIG 1.1 Users Manual. http://www.swig.org/Doc1.1/HTML/Contents.html.